Like horror and noir? Centuries ago, the English invented both.

John Martin (artist, engraver), “Creation of light” from Paradise Lost, London 1825

What do Sherlock Holmes, Dorian Gray, Tess d’Urberville, Jane Eyre, Dracula, David Copperfield, and Frankenstein have in common with the Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde? A great deal: romance, suspense, madness, mystery, fantasy, and English Gothic buildings. All belong to a literary genre named for its strong association with a medieval Catholic architectural style. So as to share recent scholarship about Gothic beginnings, Melbourne University’s Baillieu Library is exhibiting “Dark imaginings: gothic tales of wonder.” Free exhibition programs include lectures on ghost tourism, speculative fiction, immigrant vampires, and a writing workshop.

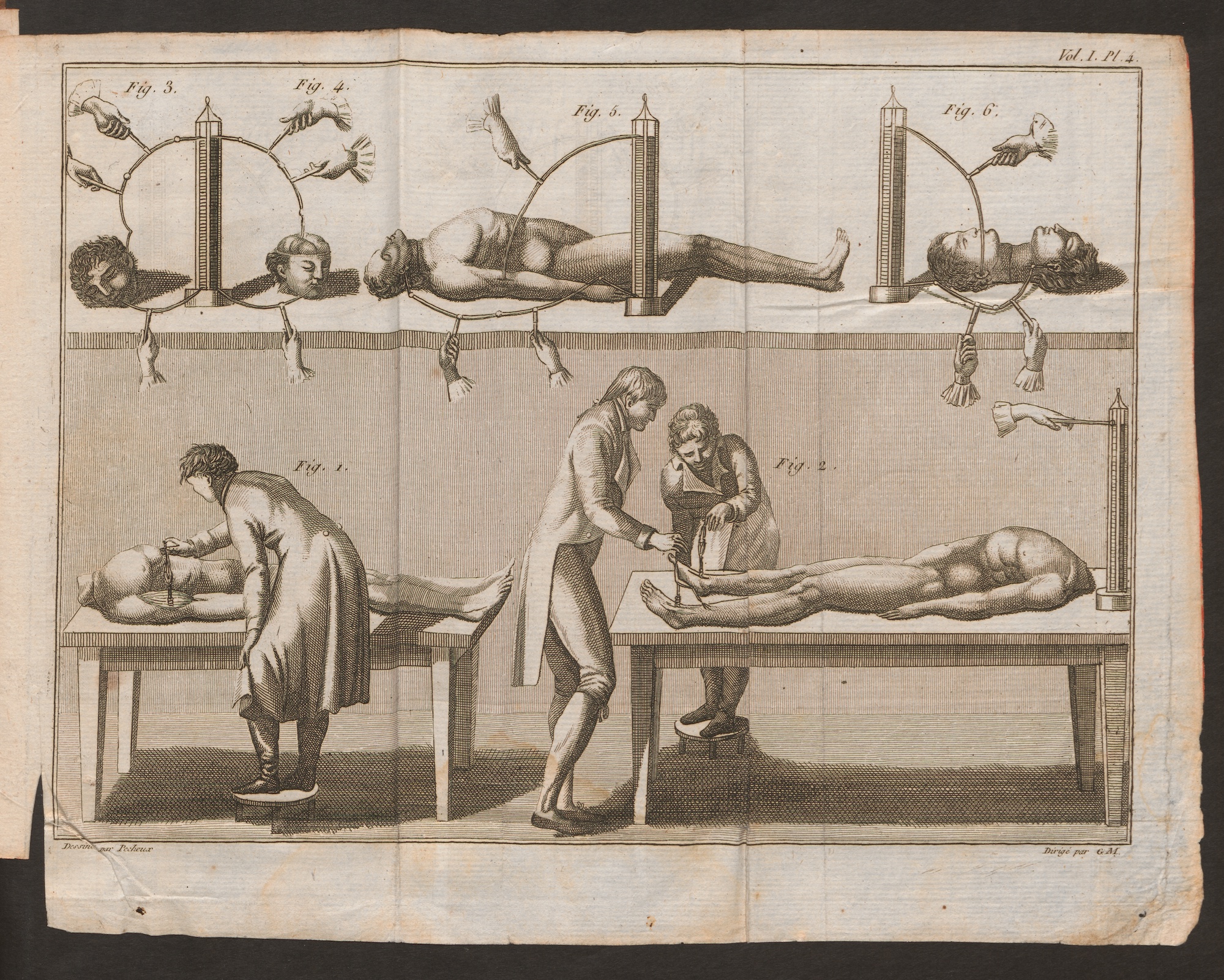

Rare books and art from the library collection have been organized by theme. Early editions of collectible gothic novels are staged as in a drawing-room. Another set is melancholic bucolic scenes from artists like Piranesi and Goya, reflecting psychological states of mind. There are publications about resurrection by electrocution (experiments which inspired Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein) and sorrowful memento mori poetics. Also included are historical projectors and trick photography that captivated a then-credulous market.

Jean Aldini (author), “Essai theorique .. sur le galvanisme“ from De l’imprimerie de Fournier fils, Paris 1804

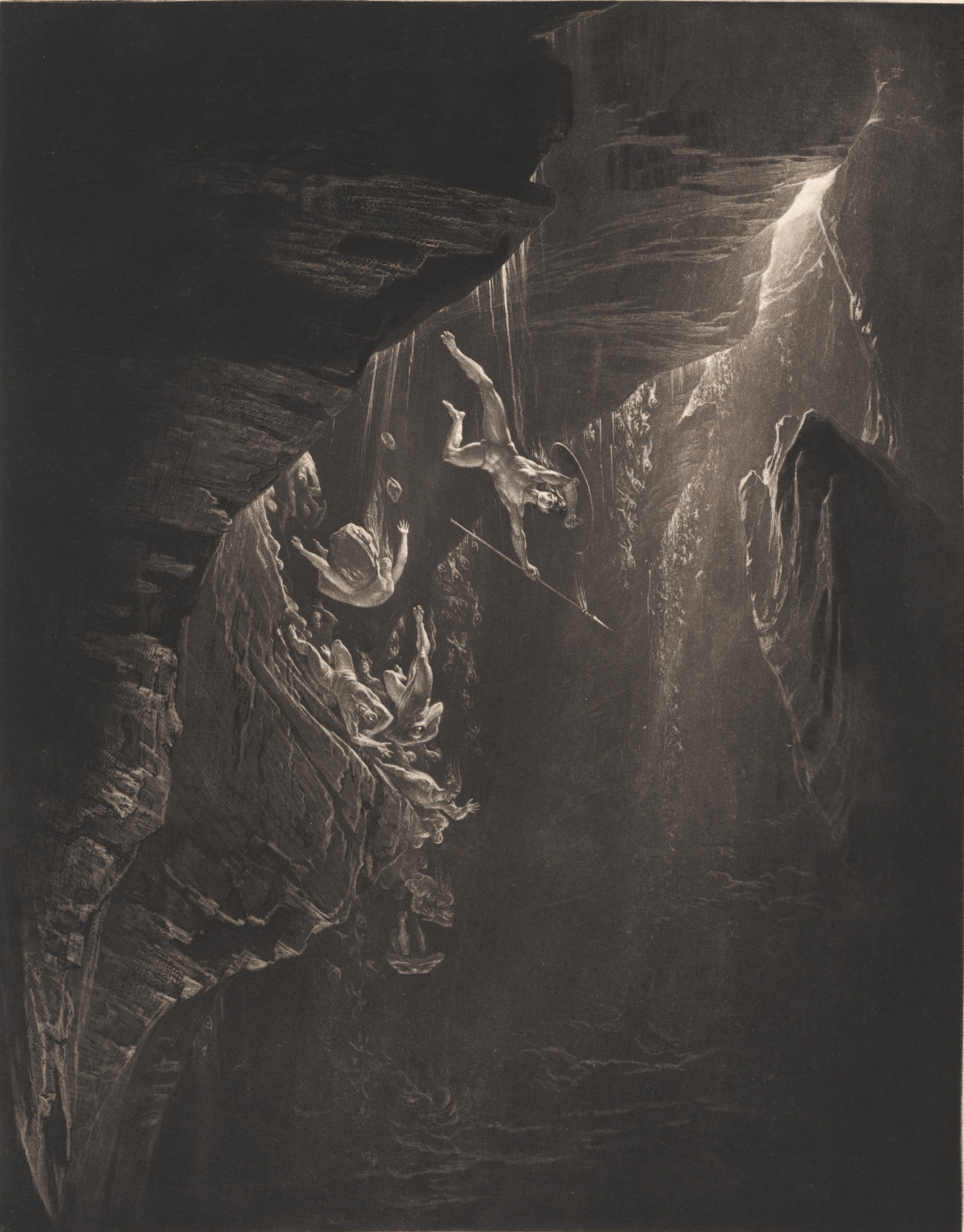

In the beginning, though, was the word. A reading public had been primed with the Bible of King James and the plays of Shakespeare. Early Modern English audiences were familiar with fallen angels and fairies; death and resurrection; heaven, hell, and dreams.

John Martin (artist, engraver), “The Fall of the Rebel Angels” from Paradise Lost, London 1826

For readers in 1800s England, Gothic ominosity was a corollary to Catholic religiosity. Forbidding and foreboding atmospherics were conveyed through descriptions about stony buildings and rocky promontories. Blackbirds caw and owls hoot. Strange, foreign, exotic flowers bloomed after midnight, under a full moon. Bad things happened to good people of heathlands and westerlands.

Robert Thornton (artist, engraver), “The Night-blowing Cereus” plate 14 from Thornton’s Temple of Flora: with plates faithfully reproduced from the original engravings, London 1807

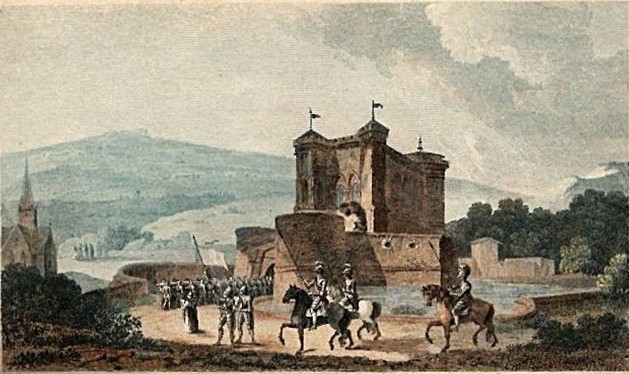

By scholarly consensus, The Castle of Otranto (Walpole 1764) is acknowledged as the first gothic novel due to its plot devices. The lord of Castle Otranto schemes to marry his dead son’s fiancée, which is an ultimately futile attempt to avert a family curse. His labyrinthine castle seems haunted. Things fall, paintings move, and doors shut, inexplicably. Purportedly a true story translated from a Crusades manuscript, its anonymous author turned out to be a medievalist politician who revered royalty.

Horace Walpole (author), frontispiece from The Castle of Otranto, London 1796

The end of the 18th century was a macabre, mawkish time for the English, since their empire was facing existential threat. There was that matter of a colonial uprising (the American Revolution, 1765-83) and a monarchy overthrown (the French Revolution, 1789-99). Much of the public uncertainty about Brittania’s future was expressed indirectly and soothed privately, through literary analogy of unknown menace. Gothic was pleasantly escapist.

But what escapism! Jekyll and Frankenstein are creators repulsed by their monstrous creations. Dorian Gray and David Copperfield are deprived youth who learn to survive and thrive. Tess d’Urberville and Jane Eyre are women betrayed by the men they love. Sherlock Holmes and Dracula personify good versus evil, or rational Englishmen versus the supernatural. These themes continue to recur in popular culture; sophisticated arcs in Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings owe much to early Gothic motif.

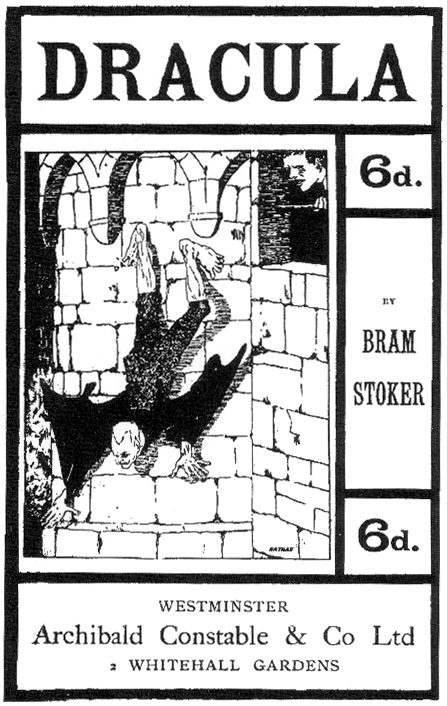

Bram Stoker (author), cover from Dracula, London 1901

The gothic masterpiece Dracula by Bram Stoker is remarkably resilient. Not only did it establish vampire stereotypes and horror tropes, elements of the story transcend period and artistic form. When the novel opens, Dracula is purchasing multiple properties in London as part of a long game to terrorise English society. A charismatic European aristocrat with mysterious powers, he subjugates victims for blood and information. His antagonists are an intrepid band led by a vampire hunter. Dracula is a feudal boyar (landowner) with a castle and gypsy servants in deepest Romania, the forested southeastern mountain region known as Transylvania.

“Here I am noble. I am a Boyar. The common people know me, and I am master. But a stranger in a strange land, he is no one. Men know him not, and to know not is to care not for.”

Stoker’s supernatural tale is an analogy of foreign invasion, written for a society anxious about threats to their way of life. More often, however, the seemingly supernatural turned out to be pleasingly paranormal, per the 1901-2 serial of Sherlock Holmes tracking The Hound of the Baskervilles. Such tales were reassuring in resolution and explanation. What was unknown became illuminated, night turned to day, and there was light.

This scholarly exhibition is a gateway to English literature, and the persistence of Gothic imagination in global storytelling.

– Maloti

Maloti writes about art and books.

Dark Imaginings runs until July 31. Exhibition public programs are free but bookings are required. Noel Shaw Gallery, Baillieu Library is located at the Parkville campus. The venue is accessible.

Images courtesy of Baillieu Library, University of Melbourne.