Long before metropolitan consumerism became the global culture that it is today, there were affiches (posters) promoting lifestyle and goods to the aspiring French middle class. Until November 4, Alliance Française is featuring a selection of posters from postwar designers in the Belle Époque tradition.

The poster aesthetic originates from the late 19th-century Belle Époque, a historical duration in France when the Eiffel Tower was built, the Moulin Rouge was founded, the Paris Métro was opened, and César Ritz launched a hotel. At this time, products and places were advertised through large-scale street posters, that celebrated consumerism and taste as much as new graphic techniques and printing technologies. As a diffused form of of fine art and lithography, posters were perceived as an art in its own right.

For this exhibition, gallery owner Brett Ross has curated affiches made by poster designers considered the last of their tradition. Ross has, over time, discovered caches of forgotten posters in storage or warehouse facilities, overstock once intended for display in Parisan public spaces. The quality of original stock is telling, for colour remains rich and the images far stronger than in print reproductions.

Perrier Fou De Soleil, 1980, by Bernard Villemot for Perrier, $675. Original lithographic poster, linen-backed, 120 x 160 cm. Villemot appropriates Fauvism and Abstract Expressionism to make product into art, and art into product.

Bernard Villemot (1911-1989) was inspired by the post-Impressionist abstract art movements, which he distilled into memorable illustration and colouration. By applying painterly tradition to advertisement — “I had but one model, one inspiration; Matisse,” he said — Villemot elevated commercial products, as well as his posters, to objet d’art. Matisse’s influence is evident in Perrier Fou De Soleil, where two embracing figures on a beach are conveyed by blocks of solid colour. Villemot’s approach was a striking departure from the typical advertisement poster, and his style was sought after by the establishment brands of Bally and Air France.

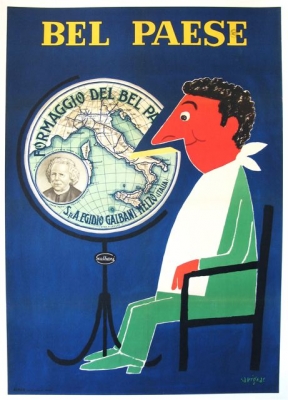

Formaggio Del Bel Paese, 1966, by Raymond Savignac for Bel Paese, $5,175. Original lithographic poster, linen-backed, 106 x 146 cm. Savignac featured consumers or producers delighting in a product, with an air more irrepressible than ironic.

Formaggio Del Bel Paese, 1966, by Raymond Savignac for Bel Paese, $5,175. Original lithographic poster, linen-backed, 106 x 146 cm. Savignac featured consumers or producers delighting in a product, with an air more irrepressible than ironic.

In contrast to the approach taken by Villemot, his friend Raymond Savignac (1907-2002) developed a singularly amusing style. Savignac’s posters are known for comic and caricature figures, a lightness initially dismissed by skeptical clients. Clients who did take a chance on him found that the buying public responded warmly to an unlikely comedy in ordinary products (yogurt, car tires, painkillers, ballpoint pens) which ensured continuing commissions over a 50-year career. He liked slapstick, and for him, “It is the taste of the gag that made me analyse the art of Chaplin.” Savignac knew his own worth, yet he would not countenance his own work as art, considering the very notion to be “nonsensical.”

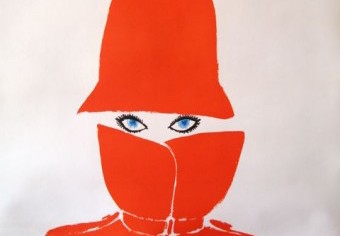

Impermeable Moderne C’est Blizzand, 1965, by René Gruau, price on application. Original lithographic poster, linen-backed, 148 x 109 cm. Gruau immortalizes Audrey Hepburn’s eyes and a Dior coat, with his signature deftness for dramatic mood.

For glamour, luxury brands turned to aristocrat and prodigy René Gruau (1909-2004) whose work remains a defining aesthetic for fashion illustration. Luxury was still an indulgence after the wars, despite the mood of optimistic consumerism. Gruau’s work is credited with stimulating aspiration and awareness of the grand couturiers from Syndicale de la Haute Couture, a delegation formalised by French legislation. Balenciaga, Balmain, Givenchy, Lanvin, and Schiaperelli courted associations with Gruau illustrations, whose effervescent linework is reminiscent of Toulouse-Lautrec lithographs. Gruau’s coverage for the house of Dior amplified The New Look, a defiant silhouette that challenged postwar austerity through extravagant shaping of fabric.

Villemot, Savignac, and Gruau are the last of a tradition that emerged from Belle Époque Paris. Fragmentation of audience markets, advertising mediums, and art movements led to a decrease in demand for this stylised form. Affiches remain a product of their age, visually arresting vignettes that capture urbane Gallic spirit. We see an imagined Paris recovering from grim history, resplendent with lifestyle choices, where happiness is just another purchase away.

Affiches runs until 4 November 2017 at the Alliance Française Eildon Gallery (51 Grey Street, Saint Kilda). The venue is accessible.

– Maloti

Maloti writes about art and books.

Maloti writes about art and books.