Gustav Mahler in the foyer of the Vienna State Opera, 1907. Photo: Moritz Nähr, Wikimedia Commons

Symphony No.9 in D by Gustav Mahler is considered one of the greatest works for orchestra, an esteem that it retains a century after it was written. For technical prowess and ambition of feeling, Mahler 9 is a demanding performance with which an orchestra’s skill is measured. It is the first major symphony of the season presented by the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, and a follow-up to last year’s Das Lied von der Erde. The MSO Mahler cycle began in July 2014 under the baton of Sir Andrew Davis, who is concurrently conducting Mahler at the Toronto Symphony Orchestra.

Mahler 9 is the only work in the program of 90 minutes without interval. Its four movements are structured with Mahler’s indications, as translated:

1. Andante comodo D major

2. Im Tempo eines gemächlichen Ländlers. Etwas täppisch und sehr derb

“In the tempo of a leisurely Ländler. Rather clumsy and very coarse” C Major

3. Rondo-Burleske: Allegro assai. Sehr trotzig “Very defiant” A minor

4. Adagio. Sehr langsam und noch zurückhaltend “Very slowly and reservedly” D♭ major

The pace of successive movements are slow-brisk-brisker-slower. In the opening Andante comodo, similar to a conventional movement, there are two main themes and recurring notes of twin harps. The string motifs which arise collapse into dissonance before reemerging, again and again. Then a second, unconventional movement follows, based on folk music that is distorted in composure. More dissonance occurs, as traditional lilts are subverted to become a caricature of dance. An apex of contrapuntal orchestration is reached in the third movement, the Rondo-Burleske. This is complicated and chaotic sound, either sophistry or sophistication of dance. It is, as the name suggests, a burlesque punctuated with the clash of cymbals. After escalation of dissonance upon previous movements, the closing Adagio is an apotheosis. It goes gently.

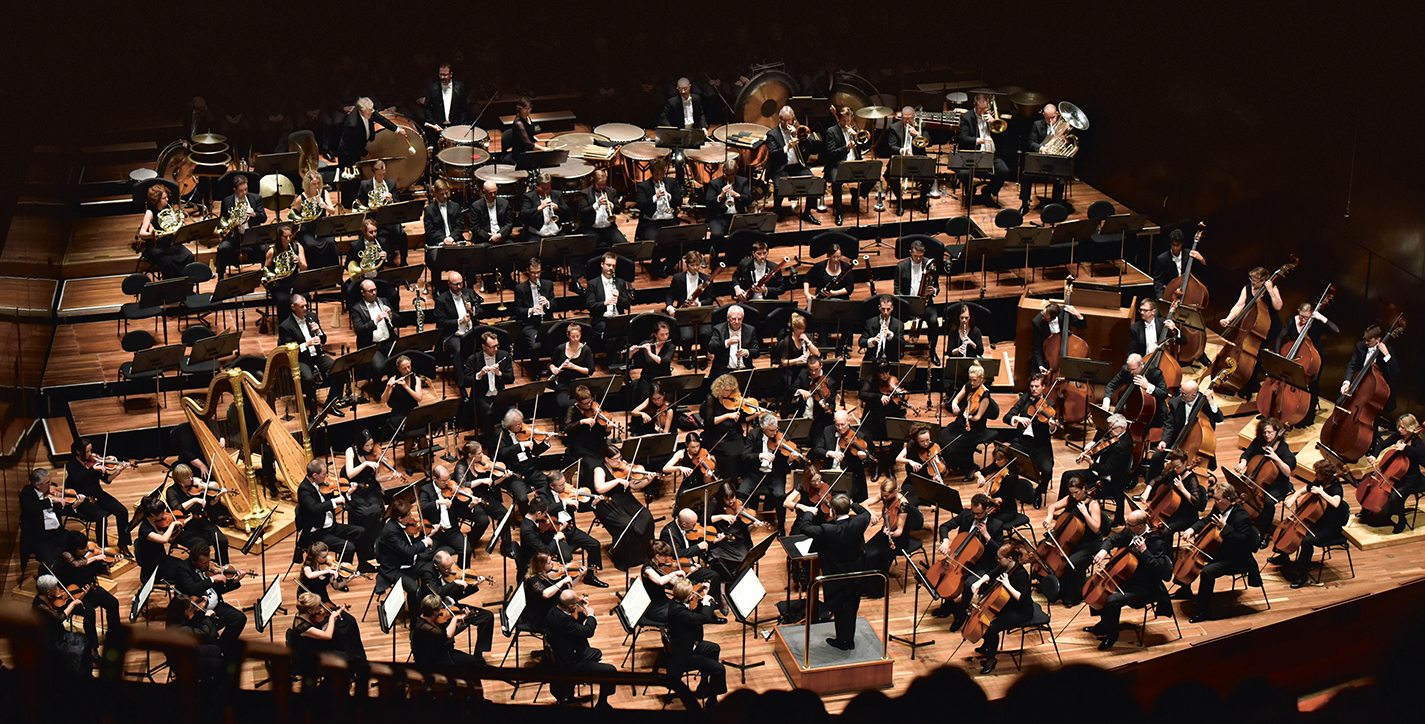

Sir Andrew Davis conducts the MSO at Hamer Hall / Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

While Beethoven’s Ninth reprogrammed the symphonic form with a choral, Mahler’s Ninth subverts consonance, which was at his turn of the century a defining identity of orchestral music. Consonance in the first movement gradually falls apart by the third. What remains in the finale is entropy.

Mahler began his Ninth in 1908, while in the midst of personal and professional crisis. He had lost his daughter and his tenure; in addition his health and his marriage were failing. Still, having left the Vienna State Opera, he was looking forward to being director of New York’s Met Opera. This symphony was a project he pursued with obsessive energy. From their summer residence in the Alps he expressed an optimistic, ecstatic outlook, writing to his wife,

“To be able to sit working by the open window, and breathing the air, the trees and flowers all the time — this is a delight I have never known till now. I see now how perverse my life in summer has always been.”

He indicated on his original manuscript score how he intended the symphony to be played. The words, “farewell! farewell!” and “dying away” are annotated. It was the last symphony he completed. Two years after, Mahler died of a terminal heart condition without ever hearing his symphony performed.

This backstory is necessary because of how Mahler 9 has been interpreted since. Notable contemporary conductors like Leonard Bernstein and Claudio Abbado have led performances that end with slowing, disintegrating notes. They represent a majority view that Mahler 9 is a sombre farewell, a symphony coloured by a finale about finality. Another view is that represented by Bruno Walter (friend to Mahler) and Rafael Kubelik, who interpret the Ninth paced less slowly. To listen to their recordings, Mahler 9 is about life still to be lived.

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra follows the former interpretation. Sir Andrew Davis conducts a finale ten minutes longer than the seminal 1938 performance (Bruno Walter with the Vienna Philharmonic) thereby reinforcing its funereality.

Mahler 9 is canonical because it redefines the features of what a symphony is. The modern symphony form originated from music for separate instruments, performed as a cohesive whole during the late Renaissance in Italy. These instrumental pieces would appear in concert with voice or theatre. Over time, pieces were restructured into standalone compositions of increasing length, for an increasing number of instruments. The symphony became seen as a higher form of musical taste, and its development intensified from the 18th-century Baroque period.

Aristocrats and aficionados believed music to be an intuitively universal language, unlimited by period or place, capable of describing the grand ineffable meanings of life. Composers who advanced the symphonic form were believed to be discovering unexplored terrain of human experience. The popular meaning of Mahler 9 is memento mori (remember death) but it isn’t the only meaning. As he progresses from tonality to atonality and the purity of silence, Mahler is remembering life. Among the last bars is a musical quote for first violins, Der Tag ist schoen auf jenen Hoeh’n! “The day is beautiful from those heights.”

– Maloti

Maloti writes about art and books.

See Mahler 9 on March 19th. The Great Classics Series continues with Tchaikovsky 5 on April 13, 14, and 16. Thomas Hampson sings Mahler, Messiaen, and Richard Strauss on June 7 and 8. All at Hamer Hall, 100 St Kilda Road. The venue is accessible.