A play about suicide. How could it be funny? With disarming bravado, four actors take us into the minds of men who have taken their lives- and what lies after the act. Michael Griffith positions us in the struggle of the aftermath in a bold take on a taboo topic in his new black comedy, Suicide Row: The Anti-Suicide Play For Men.

Produced by The Wolves Theatre’s Rohana Hayes, and sub-titled Where The Road Back Runs Through Each Other, the cast vividly renders ordinary Australian men caught in a metaphorical space where they contemplate their lives and the decision that ended it. It’s humorously told, with all the dark realism of Hamlet’s gravedigger, pulling up serious topics like bones to be spoken of, for only in frank speaking can we deal with tragedy, something this social malaise speaks strongly to.

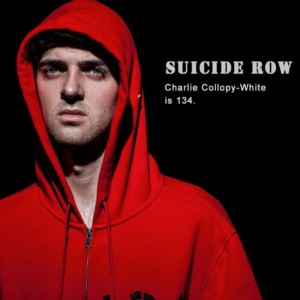

On a bare performance space, akin to a transport terminus or waiting room, we watch four men engage after death. Wearing clothes with large numbers painted on (starkly symbolising the latest statistic), they mill about, posturing, staking their space in this new territory. Life after death is a strange zone to find yourself in. Intimidating, finger-pointing, then confessing, the men employ their time waiting for …direction by revealing their life stories to each other to kill time. After death, you have all the time in the world and Griffith’s writing doesn’t shy from comic tragedy, wittily weaving it in as a key element of his work.

Coming from across all social strata and ethnicities, and across a few generations, the play reveals these men as very human beings- jocular, fragile, insecure- each with a backstory and life shadowboxing with identity and manhood. They have community ties that both connect them to the living, and which they feel torn by and leave. As with real life suicide stories, it’s painful yet truthful.

Cathartically, the play, through detailed and deft dialogue, with an excellent feel for the male voice, looks at what men express when they end their lives. Responsibility, ties, loss of face, social rejection, identity crises, an inability to cope, feeling alone with no one to consult all show up as trigger issues for male suicide. Each of these are heart-breakingly recreated in individual stories of self, family and relationship. It’s gritty material made easy in the hands of a writer brave enough to tackle the topic yet Griffith does not struggle under the negative weight of suicide. His tone is buoyant and keeps the story on an energetically elevated level, something full of life – and hope- for his male characters and for men in future crisis. The play points to seeking solutions, not blame, as a way forward, and that only in the human transaction can redemption be found.

The freedom that comes with tackling such a taboo topic is an ability to ask big questions, of life and death, and the play enjoys exploring on stage and in writing all the narrative possibilities this affords. What is the place such, or any, people go to after death? Is it heaven, hell, purgatory? A no man’s land of eternity? Is there a god who judges, or directs, you there- or only your own conscience? Is it a place for second chances, where you can reflect on your actions, the loved ones you left behind, your rights and wrongs, and whether you want a second chance? The characters sit, waiting for direction, considering such serious questions. This space is also one tempered by calm detachment, after the drama culminating in the act. It gives them the psychological relief they needed in life. One-by-one, they are picked up and sent off.

Australian statistics are alarming. Our rate is the highest it’s ever been in the past ten years, with men three times more likely to die by the means, the median age for all genders, 44 years. Aside from contributing factors such as mental illness, unemployment, homelessness, or disability, we must look at the failure of support services, personal networks, and cultural mores, to reach men during their lives and especially, in times of crisis. If asking “RUOK?” is not enough, what would be? This play gets insides men’s minds and lets them talk.

The script is punchy, funny, pointed. The writing has energy, pace, vigour, and self-deprecating humour, much like men themselves. You will recognise the man-in-the street, your neighbour, maybe someone you know. A tradesman, a psychiatrist, a business manager, and a religious runaway, their ribald jokes punctuate the newfound network they find themselves in. You will be on the edge of your seat as you listen to the characters grapple with philosophical questions. You’ll laugh at their folly as they do. There are touching stories which move, but, mainly, stories we can each relate to.

An energetic, impassioned team of actors of all ages inhabit the life of each ‘man’, presenting him with dedicated actorly nous. We know that these stories stand for so many lost and those left surviving have so many questions that can never be answered- we watch wishing to know what our loved ones thought after dying, something art can give us as life cannot. In this way, this play is a dream journey into What If but also strongly grounded in the here-and-now. Talking about real strategies to cope is what is necessary here, and the play exists in this important positivist space. The work holds hope for men.

The plot travels to a moment of unity at its nadir. The men, through talking, bond with each other. They give, and receive, trust. They reveal their imperfect selves and encounter a community of listening men. Are all men strangers til they find their commonality? the play suggests. By speaking of taboos in this afterlife, the characters are freed to be fully human, fallible, and to accept themselves, something life did not give them. Perhaps, after death, there are no expectations to live up to and we can reconfigure a different future.The play points to other outcomes that may have eventuated had these men had better acquaintance with authentic self-acceptance when living. True to it’s dramatic presentation, the story doesn’t come wholly with a happy ending just as the topic itself doesn’t, and the damage left for the living from a momentary tragic act is not sugar-coated.

The stage is a perfect forum for this social problem to be brought into the light, where deep emotions, human psychology, and stigmatised action can be aired for broader benefit, theatre’s ancient social purpose. For anyone touched by suicide, it’s the very way to have this devastating problem openly aired and provides a safe space to have ideas which trouble us all, explored. We do this for those lost to us, themselves, and the world, and for those left behind, in the midst of living after such losses, and for all people at future risk.

This play has legs. It does important work for all voices in crisis and should tour all over Australia. It follows with a debrief forum. Get down to hear an energising take on men’s realities.

– Sarah

Sarah W. is a dance-trained theatre lover with a flair for the bold and non-traditional performance platforms. On the street or in the box seat, she looks for quality works that push the envelope.

Suicide Row showed 1- 12 November (70 mins) at MC Showroom. Each showing was followed by an informal forum on the topic with cast, creatives and audience.

If you need help in a crisis, call Lifeline on 13 11 14. For further information about depression contact beyondBlue on 1300224636 or talk to your GP, local health professional or someone you trust.

Keep an eye on their Facebook page for future touring dates.

Disclosure: The Plus Ones were private guests.

Image credit: Various.